Profits are punished because they’re misunderstood

Third quarter earnings reports are trickling in this week from companies all over the nation. Some, like Ford Motor Company’s record-setting $2.7 billion in pre-tax profits in North America is good news.

Earnings reports like these are bound to stir up echoes of criticisms past, that people and companies that earn profits are doing so at the expense of hardworking Americans. As has been noted here previously, it has become almost fashionable to demonize profits. The greater the profit, the more evil or greedy those profiteers must be.

Any job creator who has ever opened a ledger knows this is not true.

As Robert P. Murphy writes in the Foundation for Economic Education’s The Freeman, “To bemoan a capitalist earning high profits is like complaining about a surgeon saving too many lives.”

Murphy says profit’s real function is misunderstood – and is defined by arbitrary terms such as “fair” or “excessive” only after it has been earned. In reality, consumers’ spending decisions drive companies to provide goods and services people want, need or desire, and profits are important “to adjust plans to reality” based on available resources. Murphy explains:

“In particular, if an investor makes an “above normal” rate of profit, it means that she anticipated future conditions better than others did. She recognized that in the original configuration, the market process was not correctly identifying the scarcity of certain inputs; they were too cheap. So this farsighted entrepreneur spotted the discrepancy and swooped in to reap the bargain. In the process, she bid up the prices of the too-cheap inputs and (by supplying more output down the road) pushed down the price of the too-expensive output.”

Ford, for example, similarly looked ahead to the future conditions and planned accordingly. Back in 2012, the automaker decided to launch a variety of new vehicles it could afford to build that would presumably roll quickly from showrooms to driveways. So the automaker began building up its inventory of new vehicles such as the F-150 pickup truck, Mustang sports car and Edge crossover, and launched them in 2014. Looking ahead, Ford achieved the right balance between its vehicle supply, the vehicles’ profit margins, what people wanted to buy, and for how much.

Had Ford over- or under-stocked supply, guessed wrongly on people’s spending preferences, or had sudden interruptions in vehicle production, its third quarter earnings report might have looked much different.

Of course this is a simplistic analysis, but Ford earned its profit because it figured out how to balance all the moving parts to a market economy, not because its leadership is greedy. And those profits will help ensure job security for auto workers while also rewarding investors who take financial risks with companies like Ford each day.

Enough people, however, still cling to the idea that profits are somehow forcibly taken from them and given to business owners. That is why we end up with government policies that punish profits rather than reward economic growth.

Corporate taxes, for instance, eat into 35 percent of profits earned by American companies.That’s the highest rate of most developed countries and enough to drive some companies to go multi-national – relocating their headquarters in countries with lower corporate tax burdens, while still maintaining a presence in the United States. Under this structure, the company can shift its U.S. income to another country with a lower corporate tax rate.

Rather than come up with ways to keep more corporate tax revenue within our borders, the belief in a mythical “fair” profit often drives calls for stricter tax avoidance laws.

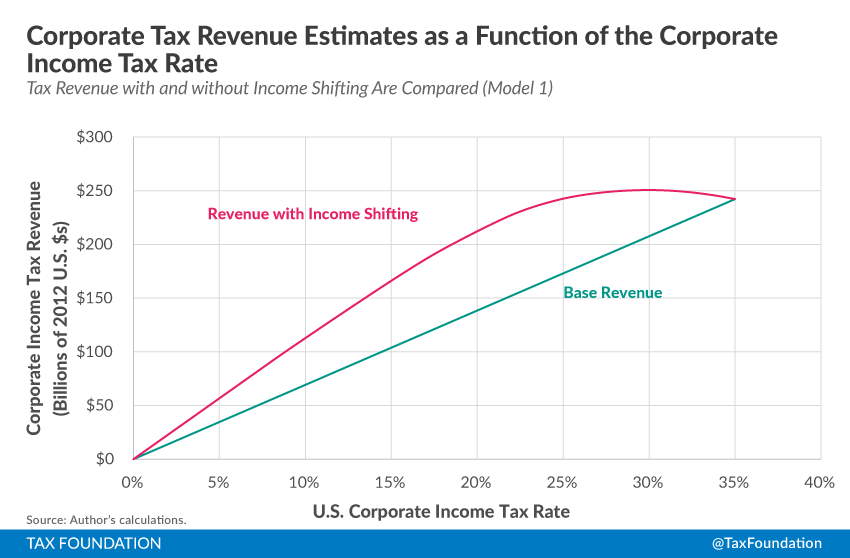

But tightening the reins on businesses shouldn’t be necessary. A new Tax Foundation study calculates that lowering the corporate tax rate to 25 percent would be enough to keep U.S. companies on U.S. soil, would increase corporate income by $278 billion, and rake in the same tax revenue as the current 35 percent rate:

“If t he empirical studies on income shifting are correct and the difference between U.S. and foreign corporate income tax rates decreases, either through a decrease in the U.S. corporate tax rate or an increase in foreign corporate tax rates, then the amount of income shifting to foreign affiliates should also decrease. Then, multinational corporations would declare more of their income in the U.S., and the U.S. would collect more revenue from the corporate income tax.”

he empirical studies on income shifting are correct and the difference between U.S. and foreign corporate income tax rates decreases, either through a decrease in the U.S. corporate tax rate or an increase in foreign corporate tax rates, then the amount of income shifting to foreign affiliates should also decrease. Then, multinational corporations would declare more of their income in the U.S., and the U.S. would collect more revenue from the corporate income tax.”

As a (hypothetical) multinational company, Ford might send its $2.7 billion profit to another country and the IRS loses $945 million it would get with the 35 percent corporate tax rate. If that rate were 25 percent, in line with many other countries, Ford’s $2.7 billion profit stays here, and Uncle Sam gets its $675 million.

Businesses that don’t fairly play by the rules should be punished. But for the vast majority of companies that do, punishing their profits with more taxes and red tape pushes them to look elsewhere for economic freedom.